This is Part 1 in a series about the Des Moines Water Works’s struggle between agriculture and water. For more background, check out the Series Overview.

NITRATE IN THE GULF

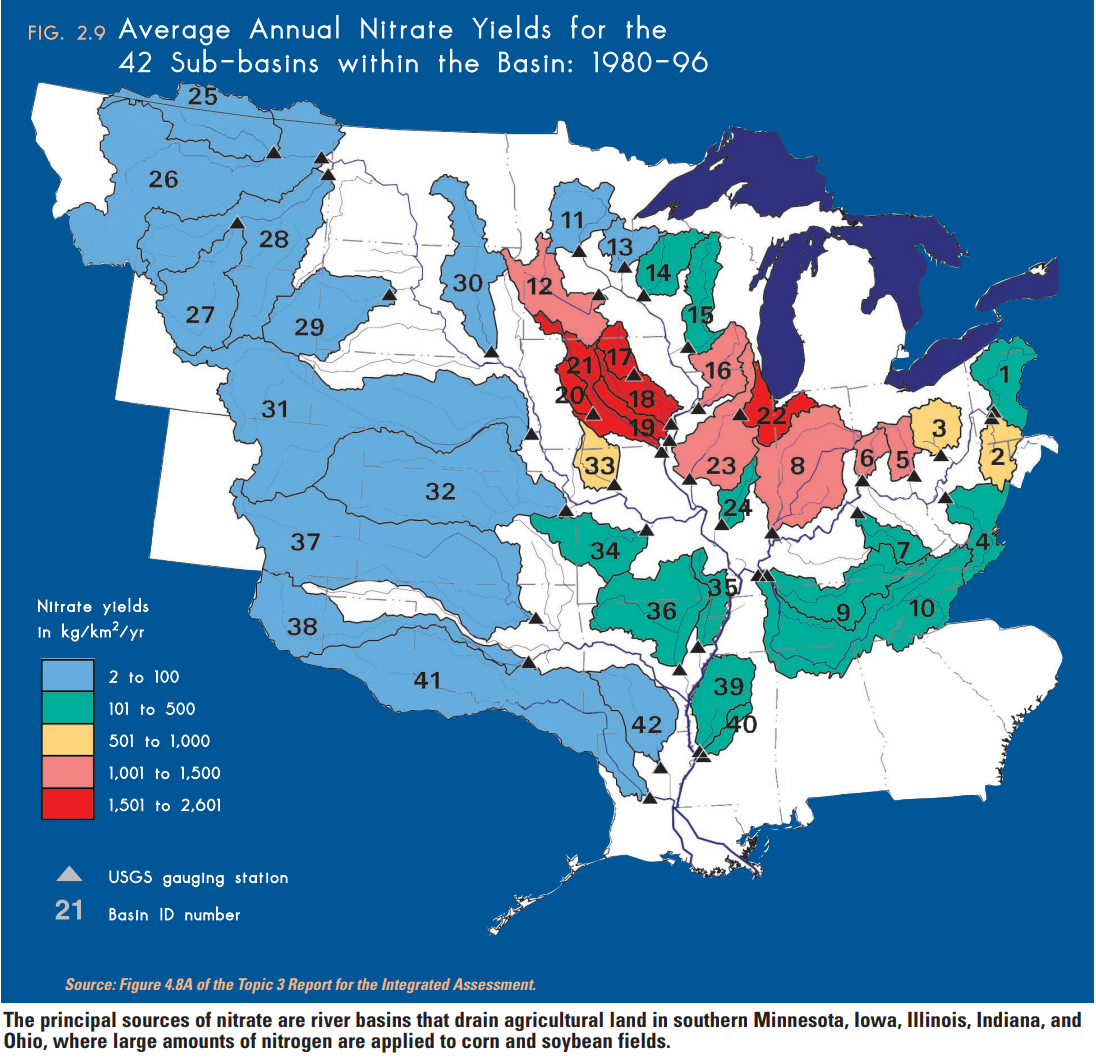

Iowa has a nitrogen problem - and has for some time now. Starting around 1960, the rate of application began to explode, increasing more than 7x in 20 years. By the 1980s the cumulative effect of all this nitrogen was a growing problem in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. When the nitrogen applied in Iowa isn’t fully utilized by its intended target (corn and soybeans), the excess makes its way to the Mississippi River and is deposited in the Gulf. All of these extra nutrients fuel the exponential growth of algae. The algae grow so fast that they consume all of the oxygen in the water, leaving none left over for fish and crustaceans.

Put simply, mismanaged nitrogen results in a direct tradeoff between Iowa Corn and Louisiana Shrimp. The more nitrogen that’s applied, the more corn that's grown, the more nitrogen that flows to the Gulf, the more algae blooms grow, the less fish and shrimp there are to be caught - Iowa Farmers profit while Gulf Fishermen lose.

By the 1990s, the Gulf community was keenly aware of this issue and in 1995 convened the First Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Management Conference. Since then awareness of the issue has continued to grow but has resulted in little meaningful impact - 2017 was the largest hypoxic zone on record.

NITRATE IN IOWA

In some sense this is no surprise because of the vast protections afforded to the agriculture industry - it is highly unregulated and even receives explicit exemptions from key federal regulations. As a point of demonstration, Iowa, the state with the highest concentrations of nitrogen, did not begin work on the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy until 2012. And when they did finally develop a strategy, it had no teeth - the recommendations are voluntary for farmers.

The EPA limit for Nitrates is 10 mg/L, and the Raccoon River has exceeded this limit every year for the past 5 years since daily measurements began in 2012 at a USGS station 20 miles upstream from the treatment plant. The concentrations typically spike between April and June, which is no coincidence as most midwest farmers plant their corn and soybean crops in April and May. At the time of planting, nitrogen is applied by sidedressing: injecting nitrogen into the soil alongside the seed.

But while nitrogen reduction may be voluntary for farmers, compliance is mandatory for all cities and towns providing drinking water (as regulated by the EPA and enforced by the Department of Justice). To maintain this compliance, DMWW was facing an $80MM upgrade to their treatment facility - $80MM solely to address excessive nitrogen levels.

NITRATE IN DES MOINES

Out of options and patience, on January 8, 2015, Des Moines Water Works (DMWW) voted to file a lawsuit against three upstream drainage districts. DMWW alleged that the districts had failed to uphold federal regulation by allowing nitrate levels in the Raccoon River to reach almost four times the concentration allowed by the Clean Water Act. This lawsuit was unprecedented due to the significant protections lack of regulation that agriculture receives.

The lawsuit that was filed two months later was based primarily on two assertions:

Under the federal Clean Water Act and Iowa Code, discharges from the drainage districts constitute point sources of nitrate pollution, which should be regulated by a National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit.

This excess nitrate pollution imposed a financial burden on DMWW, for which they should be allowed to collect monetary relief from the upstream drainage districts.

Due to the intra-state nature of the second assertion, in January 2016 the federal judge reassigned the case to the Iowa Supreme court. Fast forward a year and on January 27, 2017, the case was dismissed from court citing a century-old regulation that drainage districts have legal immunity.

Unfortunately, this is a legal technicality and mostly the fault of a poorly crafted lawsuit by DMWW. The worst consequence is that the suit was unable to force an answer to the first question: should agricultural tile drains be regulated as a point-source of pollution under the NPDES?

DMWW: A SERIES ABOUT ENVIRONMENTAL INCENTIVES

We’ll dive into this question and possible solutions in future posts, including alternative legal remedies, technological solutions, and financial structures that realign incentives between agriculture and water.

To support this series, and create solutions that benefit both agriculture and water, donate to Odd’s Creek.

References:

Successful Farming - Digging Into the Des Moines Water Works Lawsuit (2015)

EPA - National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

NOAA - The Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Watch

NOAA - The Causes of Hypoxia in the Northern Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico Program - Proceedings of the First Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Management Conference (1995)

NOAA - Gulf of Mexico 'dead zone' is the largest ever measured (2017)

Iowa State University - Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy

Iowa State University - Iowa Supreme Court Sides with Drainage Districts (2017)

USGS - Daily Nitrate Recordings from the Raccoon River (2012-2018)